Brittney Ingersoll

Today, old photographs can be found in attics, basements, antique shops, and even archives that showcase people whose identities have been lost to time. Although their names may be gone, we can still learn so much from their pictures. The details of the images themselves and the types of photographs provide information that allows us to better understand the past. While it would be helpful to know who the people in the photographs were, the photographs still have historical value.

Types of Nineteenth-Century Photographs

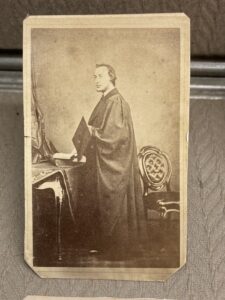

The nineteenth century was the century of photography. The first type of photography available was the daguerreotype (c. 1840-1860), which was highly expensive, making them only accessible to the wealthy members of society. Due to their value, the photos were not simply tools to capture images of loved ones, but they also reflected the financial status of those who could afford to have their picture taken. Daguerreotypes phased out to more affordable forms of photography: (in chronological order) tintypes (c.1856-1867), carte de visite (c.1854-1910), and cabinet cards (c.1867-1895). Each is more sustainable than daguerreotypes, which were made of glass and incredibly fragile, as well as prone to fading – losing not just the names but sometimes the faces as well. (1)

Tintypes followed daguerreotypes and were, as the name suggests, developed on thin sheets of tin. Tintypes can be found in very small sizes – leading one to question their size and if they were made for a certain purpose. Not all were created with the intent to be put on display in the traditional sense. Some tintypes were cut very small to be used in brooches and/or lockets. Images of loved ones could be worn and carried with the person. Their size provides clues to the photo’s purpose. Was the tintype made for a lover’s locket, to be kept with them at all times? (2)

Reading the Images

While identities may be lost, much can still be gained from the images themselves. Scholars have developed a form of study called “Visual Culture,” defined as “…the study of the social construction of visual experiences, and also the visual experience of social constructions.” (3) Through the study of images, one can learn the social standards and beliefs of the time as well as the significance of the images within that society. Images at their most basic level are just shapes and lines, constructed together to create different meanings and ideas. Through visual culture, images, like written documents, are analyzed to gain a more complete understanding of the past. (4)

For example, one can gather what people found important or how they wanted to present themselves through the analysis of photos. People displayed their status through the items they purchased and possessed. Nineteenth-century sociologist Thorstein Veblen coined this phenomenon “conspicuous consumption,” the process in which people purchased items to proclaim their status and association with the middle-and upper -classes. People would dress their best in photographs that were then put on mantels and displayed in homes, further reinforcing their position within society. These symbolic items of wealth were also potentially meant for the photographer, to help demonstrate that they were not capturing the image of an average person. (5)

Photos in which people wore their best clothing was potentially a message of who they were and where in society they belonged. They also could have used photographs to claim a higher status by posing in their best attire and implying they were more wealthy than they were. This would make the photograph a tool for lower-class people to reflect their aspirations. (6)

Some photographers possessed costumes and props for people to dress up and take on personas and identities that were unlike their own for the pictures. But, why? Why did people wish to dress up and be someone else? So much can be surmised – was it purely for fun? Did it give them a chance, even for a moment, to escape from their own lives? How different was their character versus their reality? Did the costume allow them to feign power that was unattainable due to class structures, racism, and or sexism? Dressing up may have been strictly for fun for some, and it may have been a moment of escape for others. And if it was an escape, what does it tell us about the world those in the photographs existed in? (7)

Conclusion

Photographs without names are pretty common within the Cumberland County Historical Society’s archives. Local families donate old photos of past family members, but other than a possible familial association, little additional information is known. Sometimes family associations are unknown. While names and exact dates may be lost, so much can still be learned from these photographs. Just look closer!

Sources:

(1) Janice G. Schimmelman, “The Tintype in America 1856-1880,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol. 98, No. 2 (2007); “What is a Daguerreotype?” Daguerreobase, http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/knowledge-base/what-is-a-daguerreotype ; Tracee Hamilton, “How to Date Old Photos,” AARP, https://www.aarp.org/relationships/genealogy/info-11-2011/dating-old-photos.html ; Colin Harding, “How to Spot a Carte de Visite,” The National Science & Media Museum, https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/find-out-when-a-photo-was-taken-identify-a-carte-de-visite/

(2) “Ambrotypes and Tintypes,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/liljenquist-civil-war-photographs/articles-and-essays/ambrotypes-and-tintypes/

(3) “Introduction” A Critical Overview of Visual Culture Studies: Seeing High & Low : Representing Social Conflict in American Visual Culture, Patricia Johnson, Ed. (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006), p.2

(4) Ibid.

(5) Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, (New York: Penguin Books, 1994).

(6) John Berger, “The Suit and the Photograph,” About Looking, (New York: Pantheon Books, 2011).

(7) Janice G. Schimmelman, “The Tintype in America 1856-1880,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol. 98, No. 2 (2007).