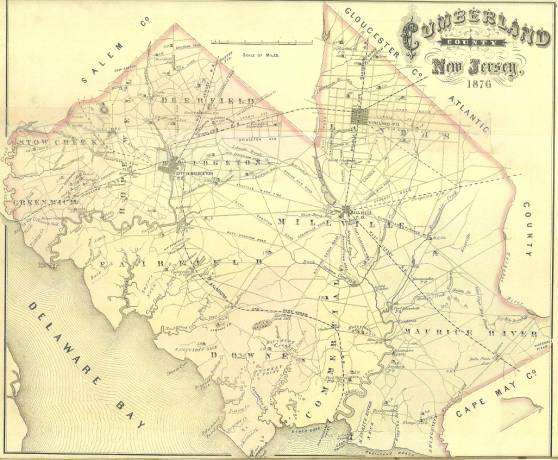

Cumberland County Early Industry

Early Industrial Revolution in Cumberland County

- Bridgeton

- Indian fields Run

- East Lake

- Millville

- Union Lake

- Columbia Avenue

- Cedarville

- Fairton

- Port Elizabeth

- Stow Creek

Grist and Saw Mills

Gristmills and sawmills were among the earliest local industries, built on outlying creeks and rivers, and in Bridgeton and Millville where they marked the first sign of settlement. Tide mills powered by the ebb and flow of the creek waters existed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

One of the earliest was Hancock’s Sawmill, built in 1686 on Mill Creek (Indian Fields Run) in present-day Bridgeton. Richard Hancock also constructed a dam and mill here, which changed hands several times until 1807-08, when Jeremiah Buck bought them and built anew on Commerce Street. These and other mills were especially important because they predicated the establishment of Bridgeton. Farther east, another dam and mill played a similar role in the development of Millville.

In 1776 the Union Company was started by four Quakers from Burlington who purchased 24,000 acres near Millville from William Penn’s sons. The company used the dam to power sawmills; the lumber was then floated down river where it was loaded on to ships bound for market. In 1795 Joseph Buck, Eli Elmer, and Robert Smith bought the Union property. Buck then planned the city of Millville—slated to contain mills and other industries fueled by water passing over the dam. Many mill and factory owners here gained access to the nearby waterpower by digging canals to their property.

Buck’s plans for the city became reality when David Wood and Edward Smith established Smith and Wood Iron Furnace. Wood’s brother, Richard, added to the family prosperity by establishing a cotton mill next to the foundry in 1854. Wood then constructed a new dam, creating the largest manmade lake in New Jersey. The water power from the dam allowed the mill to produce its own electricity in the late nineteenth century. By 1870 the mill had 25,000 spindles, 500 looms, and 600 employees. Thirty-nine years later the number of employees had doubled.

Many Millville Manufacturing employees lived in homes constructed by the Wood family in the surrounding area. Moreover, they shopped at the company store located on Columbia Avenue next to the Wood Mansion. The company also constructed a wood bridge across the Maurice River to shorten the distance for those workers who lived on the western shore. Though the worker housing exists today, many of the industrial buildings associated with Millville Manufacturing do not. However, buildings connected with the foundry exist, including the pump house used by the cotton mill.

Like Bridgeton and Millville, the mills elsewhere in South Jersey encouraged settlement, and provided jobs as well as independence from Great Britain. In 1702 John Mason of Elsinboro built a flour mill on Stow Creek; about the same time Samuel Fithian erected a dam and sawmill in Fairfield, his son John, who lived nearby, co-owned a gristmill. The Fithians’ property was acquired by John Ogden, then in 1743 by David Clark who moved the gristmill to the main road in Fairton, bringing in water via a mill race. In 1759 the mill dam in Fairton was changed to its present location.

In Cedarville, Henry Pierson purchased a mill from William Dillis and John Barns in 1753, which henceforth changed ownership many times. Also nearby was the sawmill and gristmill John O. Lummis acquired in the 1830s; the former was built before 1789 (perhaps replacing an iron foundry), the latter was built in 1790.

Windmills and steam mills were also popular in South Jersey—for grist and lumber—found primarily in Cape May County and occasionally the Leesburg area of Cumberland County. The earliest one was built for Thomas Press in 1706 on Windmill Island below Town Bank. The last extant example existed in Leesburg in the 1920s.

By the nineteenth century, mills were common to almost every South Jersey town. According to the Gazetteer of the State of New Jersey, in 1834 Cumberland County had forty-four gristmills, twenty-one sawmills, and one each fulling, rolling and slitting mills.

Early Glass Industry

The glass industry is one of the oldest and most successful industries in South Jersey—and one of the few in the area that remains. South Jersey was the natural setting for a widespread glass industry due to the abundance of sand, forest, and navigable waterways. One of Salem County’s celebrated roles in history is that it is home to the first successful glass factory in the nation.

In 1738 Caspar Wistar, a German immigrant and Quaker, laid out his new glass factory, a complex composed of a cordage pot, glass house, general store, workers’ housing, and his mansion. The last three were essential, as the closest town was six miles away. Moreover, Wistar had more influence over his workers if they lived in housing he provided.

Wistar also needed professional glass blowers, and he willingly made them partners in his firm. He invited Caspar Halter, Johan Halter, Johann Wentzell, and Simon Greismeyer from Germany. In exchange for their glass formulas, he provided one-way passage, land and dwellings, servants, and one-third of the company profits. The town became known as Wistarburgh and its product, Wistarburgh glass.

Wistar’s son, Richard, eventually took over the company, which relied upon skilled glassmaking immigrant labor. The demise of Wistarburgh came with the Revolutionary War, though exactly why and when is unknown. Some historians speculate that it closed in 1776 because the workers were drafted by the American army.

Other prominent glass factories were based in Port Elizabeth, Bridgeton, and Millville where there was access to sand, woods, and waterways.

The Eagle Glass Works, built in 1799 in Port Elizabeth, was the third glass house established in New Jersey. James and Thomas Lee, with a group of Philadelphians, founded Eagle Glass on the Manumuskin Creek, a branch of the Maurice River. The company hired several members of the Stanger family, highly skilled bottle-makers, though the first furnace was devoted only to making window glass.

From 1816 through the 1840s, another well-known German glassmaking family—the Getsingers—rented Eagle Glass. After several subsequent owners, the glassworks was sold at auction in 1862; it did not operate long, however, and was abandoned by 1885.

The Union Glass Works was established between 1806-11 by Jacob and Frederick Stanger, and William Shough; Randall Marshall joined them as a partner in 1811. Union Glass Works closed in 1818. [8]

After setting up the Eagle Glass Works in Port Elizabeth, James Lee established the first glassworks in Millville in 1806, on the Buck Street site which was later run by Whitall Tatum and now is home to the American Legion. Known as Glasstown, Lee produced window glass here. Finally, in 1901 it was incorporated as the Whitall Tatum Company.

In addition to Glasstown, Whitall Tatum bought a glassworks on the south end of Millville in an area called Schetterville. The Company originated in 1832 and today Foster-Forbes, a division of American Glass, owns this part of Whitall Tatum. Millville was a center of glassmaking during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Bridgeton was a relative newcomer in comparison, hosting glass furnaces from the middle of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth.

Nathaniel L. Stratton and John P. Buck started the Stratton, Buck and Company glass factory in Bridgeton in 1836 at Pearl Street and the river. Many of the flasks it produced were impressed with “Bridgeton, New Jersey.” This company represented the single-largest business in Cumberland County for many years thanks to holdings of large tracts of land and a general store. After many hands the company incorporated in 1870 as the Cohansey Glass Manufacturing Company, makers of fruit jars and window glass.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Bridgeton was home to more than seventeen glass factories, operating at various times. These included: Getsinger and Son; Cumberland Glass Manufacturing Company/Clark Window Glass Company; More, Jonas, and More Glass Works; East Lake Glass Works/Hollow-Ware; Parker Brothers Glass Factory; West Side Glass Manufacturing Company Ltd.; Perfection Funnel Works; Glass-Bottle-Mold Factory; and Daniel Loder. Their products ranged from fruit jars and bottles to funnels and windows.

Canning Factories

The first canning factory in Cumberland County began in the 1840s at the home of John E. Sheppard, Greenwich, who lived conveniently near the Quaker meeting house where town’s-women helped with the labor. Like many early canneries, Sheppard made the cans on the premises. Local historians surmise that Sheppard also did some canning in a house near Sheppard’s Mill, two miles outside of Greenwich.

Over the century or so from 1840 to 1942, Cumberland County hosted about twenty-eight different canneries at various times. The greatest influx of new canneries and related businesses occurred from 1860-90, when approximately twenty-three new canneries began operating: thirteen in Bridgeton, two each in Fairton, Cedarville, and Greenwich; and one each in Bacon’s Neck, Bayside/Caviar, Millville, and Newport.

Stein Edwards established the first cannery in Bridgeton in 1861, named after himself. Six years later he sold it to Warner, Rhodes and Company and in 1888 it was merged into the West Jersey Packing Company, which made its own cans and packed about 700,000-1 million units per year. Warner Rhodes specialized in tomatoes and peaches, but it also packed lima beans and sweet potatoes, and manufactured ketchup and salad dressing.

Millville had at least three glassworks by the mid nineteenth century, as well as an iron foundry; Bridgeton had several glass companies and a machine factory. Greenwich also had a machine factory, James Ayars, owner and operator of Ayars Machine Shop of Greenwich.

Iron Foundries and Machine Factories

The R.D. Wood and Company foundry began as a complex on Columbia Avenue in Millville. Originally founded by David Wood and Edward Smith in 1814, it was first called Smith and Wood. The foundry, along with the Millville Manufacturing Company—also owned by Wood, across from the Wood Mansion and the company store—obtained its power from the Union Lake Dam. By the end of the nineteenth century, R.D. Wood and Company employed 125 people.

A year after the establishment of the Smith and Wood Foundry in Millville, Benjamin and David Reeves started the Cumberland Nail and Iron Company in Bridgeton. Located on the west side of the Cohansey River, this ironworks obtained its power from the nearby Tumbling Dam. In 1856 the foundry became the Cumberland Nail and Iron Company. At the end of the nineteenth century, the company employed 400 men and produced 40,000 kegs of nails and 4 million feet of pipes yearly.

Foundries in Cumberland County were numerous in the eighteenth century in remote areas. The earliest-known foundry was on Cedar Creek outside Cedarville. Local historians believe it existed before 1753, when a sale notice appeared in the newspaper:

In addition to being located on Cedar Creek, which was dammed to create several ponds for power, the foundry was located near a forest and a swamp. By 1789 it no longer existed and the ponds were used to run Ogden’s Mill. Again, local historians believe the foundry folded due to the depletion of bog iron.

Eli Budd built Budd’s Iron Works in 1785 on the Manumuskin Creek. They became the Cumberland Furnace in 1812 and after several changes in ownership, the furnace was sold to R.D. Wood in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Today little evidence remains of the iron industry in Cumberland County, but for the exquisite ironwork found in the fences, cresting, and other architectural features that highlight church yards and older residential areas. The key to the success of many of these nineteenth-century foundries was their ability to take advantage of the economic possibilities made available by South Jersey’s unique geographic location and combination of natural resources. Eventually, depleted woodlands and changing technologies contributed to their decline.