By Victoria Scannella

In the early days of the American Revolution, prior even to the writing of the Declaration of Independence, interest in education was being taken up by those living in Southern New Jersey. As early as 1773, a man named John Westcott created the first private school in the state. Continuing on this path, the pastor of the Greenwich Presbyterian Church, Reverend Andrew Hunter established a classical school in Bridgeton, from 1780 to 1785. (1) In addition to these efforts, the Quaker population also had a vested interest in early education efforts in New Jersey.

The Quakers followed a religion of pacifism and an easy way of life, with religious freedoms and with the hope and promise of economic prosperity in the newly settled land of what was then called West Jersey. It was the Quakers who voiced opinions regarding the importance of education, specifically Thomas Budd, an early Southern New Jersey Quaker. Budd’s opinions were published in Good Order Established in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in America: Being a True Account of the Country in 1685, suggesting two separate types of education for boys and for girls, in addition to parents being legally required to send their children to school. For the boys, Budd proposed that they be educated in subjects such as reading, writing, arithmetic, and bookkeeping, whereas the girls should learn home-based skills such as spinning, weaving, knitting, and other similar subjects. (2)

Starting in 1794, the New Jersey Legislature passed an Act that would provide for the establishment of “Societies for the Promotion of Learning.” (1). The fund grew over time, and eventually, taxes were used to add to the fund. In this article, I will cover those schools that were the most prominent and/or had the most impact on the history of early education in South Jersey.

Prior to the legislation of education by the State of New Jersey, it was up to the individual townships to establish school and/or education systems. In the 1870s, there were various fundraisers and attempts to raise money with the intention of creating a school and being able to pay those who would teach there.. Additionally, this is around the time the first law in New Jersey was established, requiring parents to send children from the ages 7 to 16 to school or get educated elsewhere (such as homeschooling). (2)

The Old Stone Schoolhouse, built by the Quakers in 1810 in Greenwich in Cumberland County, is the oldest officially known school building in Cumberland County. The building is still standing, living as the oldest school in the county. Not only did it serve as a school, it also was used for militia training, a town hall, among other things. This building is not currently in use. (3)

The idea for a new academy exclusively for boys was brought before the Presbytery of West Jersey in 1850 by Reverend Dr. Samuel Beach Jones. The project was taken on and the school opened in 1854, serving students of Cumberland County until around 1910, when it appears as though the Academy was sold by the Presbytery of West Jersey. The land and the building were purchased by the Bridgeton Board of Education. In the book The Bridgeton Education Story, A Historical Souvenir of the Bridgeton, New Jersey Tricentennial 1686-1986, it was around 1910 that the Academy “fell victim to the high school movement.” In which the establishment and differentiation between types of schools became more prominent, describing the youngest school age as primary, middle age as secondary, and grammar school as the highest level. Later on, it was referred to as a “high school,” shortened from “high grammar school,” indicating that it was the highest level of school before college. (1) With the creation of Bridgeton High School in 1929, the original front facade of the Academy remained in use by the new school, and other parts of the building were added behind it.

There were two private schools intended for girls, Ivy Hall Seminary and the Seven Gables School. Ivy Hall Seminary was founded by Margaretta C. Sheppard, as a boarding school for the young women of South Jersey. The original building was built by David Sheppard, a farmer living in South Bridgeton, in 1791. (4) In 1850, fathers of Bridgeton who wanted their daughters to become educated rented the second floor of the General Store that was across the street, owned and operated by Sheppard’s youngest son Isaac. Teachers were hired from New England to educate the daughters with the overarching intention of starting a school for girls. Isaac Sheppard’s third wife Margaretta, having attended the first institution of higher learning for women (which falls in line with a college), became strongly invested in establishing a seminary in Bridgeton, having been trained in education while at the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary.

After marrying Isaac Sheppard, it was in 1861 that Margaretta opened the school in the Sheppard House, first known as the Bridgeton Female Seminary, Family and Day School for Young Ladies. Later the name was to become Ivy Hall Seminary, as it is remembered today. It remains unclear if Ivy Hall took the place of the school formed by the fathers, but given it was in the Sheppard House, it can be assumed that it took the place of the former school.

It was from Margaretta and Isaac’s own home that the school functioned. (1) Isaac’s daughters stepped in to help Margaretta, and subjects such as geometry, chemistry, and moral philosophy, among other subjects and languages, were taught at the school. Young women were drawn from all around the country to attend the Seminary, even following Margaretta’s death. Not only was this school created for women, it was also extremely important in the emerging suffragist movement. Interestingly, “Ivy Hall was a venue for independent young women to teach progressive students the importance of women’s rights. One student, Ella Reeve, later Ella Reeve Bloor, became a Progressive Era leading light, working for temperance, women’s suffrage, and workers’ rights” (4). Following its time as a school, it was in 1919 that the property was sold to Dr. Reba Lloyd and the building became known as Ivy Hall Sanitarium. The sanitarium provided care to everyone, including practice in maternity. The sanitarium was in operation until the 1960s when it became a retirement home. (4) Despite closing in the early twentieth century, the school still seemed to have a profound impact on the women of South Jersey.

The Seven Gables School was also a school for girls, similar to that of Ivy Hall Seminary. Founded by Mrs. Sarah Westcott following her husband’s death, Sarah had been conducting a young girls’ seminary in Camden, New Jersey, before coming back to Bridgeton to open her own school, in 1886. This was done out of her own residence on Lake Street. The graduation ceremonies were held every June at the West Presbyterian Church. Seven Gables was closed and the property was sold by Sarah in 1896. The property later became Lake View Sanatorium for Chronic, Medical, and Nervous Diseases.

The South Jersey Institute opened in 1870, existing as a boarding school for both boys and girls, until it closed in 1907. The school was under the jurisdiction of the West Jersey Baptist Association. The purpose of the South Jersey Institute was to prepare its students for college by giving them a well-rounded education. Coeducation was unique for this time. It is unclear how or why the school closed. Before deciding on the West Jersey Academy land, the Bridgeton Board of Education considered buying the Institute property with the intent to build the later public Bridgeton High School. The building was later demolished and there are now homes on the former property of the school. (1)

Salem had a few private schools, the first one was established in 1818 by the Johnson Family who gave the property that the school came to exist on in 1787. It remains unclear, aside from language classes, what other classes were offered at the school. The languages offered were English, Latin and Greek. This school lasted into the twentieth century, specifically when remains unclear, as does the reason that the school closed. The building later became home to several seminaries during the 1820s, one being operated by a man named Joseph Stretch and another run by the Baptist Society.

Salem Collegiate Institute was established in the Rumsey Building, founded in 1867 by Reverend George W. Smiley. The school opened as a girls’ school but eventually began admitting boys. It was two years later that the school was purchased by John H. Betchel, and 90 students were enrolled. During Betchel’s time there, student enrollment increased by one-hundred. A professor by the name of H.P. Davidson purchased the school in 1872, despite the local reform group pushing back against it. Davidson helped the education of the students by creating the curriculum in a systematic way, in addition to offering hands-on learning to further improve the students’ education. The school closed late into the nineteenth century, doing well up until the point of closure. (2) A few years after the end of the Civil War, Lawmakers in New Jersey began education reformation in the state. This reformation began with the New Jersey Legislature in 1867, with the help of congressional bodies,

The Constitution was amended to “provide for the maintenance and support of a thorough and efficient system of free public schools for the instruction of all the children in the State between the ages of 5 and 18 years.” A ten-member State Board of Education was appointed by the governor, and provisions were made to appoint an education commissioner. Moreover, plans were made to maintain a normal school and a model training school, and to set up a board of examiners to review and license teachers. (2)

Bridgeton was the first urban area to actually establish a public-school system. It served specifically white children who were age seven and older, but due to limited space, only 2 children per household were permitted to attend. During this time there were only twelve public schools in New Jersey that were free to attend.

There is significantly less documentation regarding school for black children in Southern New Jersey. In Southern Bridgeton there is a known existence of a one room school for black children, and ten years later there is one that was documented as being part of a survey performed by the county, but it is unclear if they are the same school. (2) Following this, during the middle to late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the existence of schools and school buildings grew significantly in New Jersey. Rural New Jersey schools and “the majority of extant country schools are lookalike, modest, gable-roofed frame buildings constructed of commercially produced and dimensioned materials and manufactured hardware, but incorporated provincialized ornamentation; many have been adapted to a new use. The forms, built from the mid to late 1800s, are repeated in nearby churches, community centers, granges and masonic halls.”(2) Once schools became a mandated thing for those living in the State of New Jersey, it became increasingly common for multiple schools to exist in one town. In fact, almost every single town had its own school. (2) Present day, there are around 2,511 schools in New Jersey. Local Educational Agencies, consisting of Charter Schools, Operating School Districts, Non-operating School Districts, among others, there are 697. (6) New Jersey is also home to around 83 schools, 51 being private and around 32 public Universities. (7)

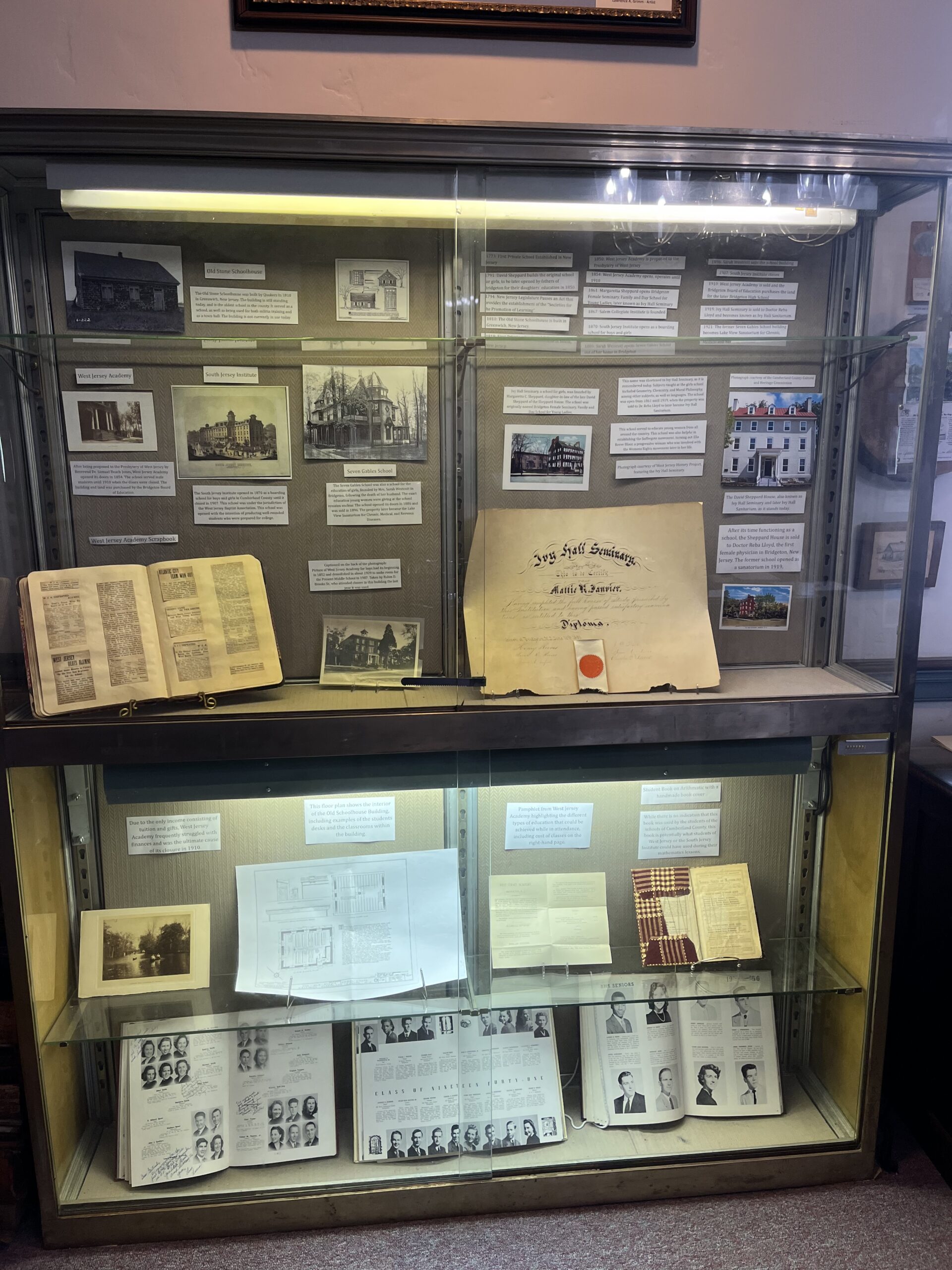

Come check out the physical exhibit at the Lummis Library! The photograph features the exhibit, complete with objects and information regarding the history of education in early Cumberland County. The very bottom of the exhibit features Bridgeton High School yearbooks, from years 1939, 1941, and 1956 for a more modern look at education in Cumberland County.

- J. Robert Buck, William J. Chestnut, Joseph C. De Luca, and Robert L. Sharp. “The Bridgeton Education Story, A Historical Souvenir of Bridgeton, New Jersey, Tricentennial 1686-1986.” (n.d.)

- Kimberly R., Sebold, and Sara Amy Leach, “Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route: Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties §” (n.d.). http://npshistory.com/publications/new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap7.htm

- “Old Stone School House” Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, NJ.GOV Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.nj.gov/dca/njht/funded/sitedetails/old_stone_school_house.shtml

- Matthew E. Pisarski, “David Sheppard House.” Cumberland County Cultural & Historical Commision. Accessed July 10, 2023. http://cumberlandnjart.org/cumberland-historic-sites/david-sheppard-house/

- Jacob Downs, “Female Education in Camden County: 312 Cooper Street – Young Ladies’ Seminary School.” Cooper Street Historic District, March 11, 2018. https://cooperstreet.wordpress.com/2013/03/29/female-education-in-camden-county-312-cooper-street-young-ladies-seminary-school/

- “New Jersey Department of Education.” New Jersey Public Schools Fact Sheet 2022-2023. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.nj.gov/education/doedata/fact.shtml

- “Colleges & Universities in New Jersey: 2023 School Guide.” Colleges & Universities in New Jersey | 2023 School Guide. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.franklin.edu/colleges-near/new-jersey#:~:text=There%20are%20at%20least%2083,54%2C601%20undergraduate%20students%20were%20enrolled

- Bridgeton Evening News, A Souvenir of Bridgeton, New Jersey. (1895).