Brittney Ingersoll

In 1870, George Henry Whipple and Edwin F. Brewster started Whipple & Son Drugstore in Bridgeton, NJ on the corner of Broad and Fayette Street. Although the partnership was short-lived, with Whipple purchasing Brewster’s interest in the company only a year later, the store flourished into a successful operation for a number of decades. Whipple’s store sold a variety of medicines, some being patent medicines. Patent medicines were easily accessible and affordable cure-alls, that promised amazing health and healing in a bottle. While patent companies made promises of grandeur, the promises tended to be empty with either the individual continuing to suffer, die, or heal on their own. ‘Quackery,’ ‘nostrum,’ ‘tonics,’ and ‘pseudo’ are some of the words used to either describe or synonymous for patent medicines. Historian James Harvey Young described the popularity of patent medicines and medical quackery as being “Aided by medical ignorance and a remolding of economic patterns, shrewd entrepreneurs, pioneered promotional techniques which, in the atmosphere of Jacksonian democracy, were expanded and elaborated as the common man sought common relief for his common ailments.”(1) Whipple and many others who earned an income from patent medicines were able to do so due to the development of capitalism, consumerism, growth of distrust and anti-intellectualism, and the lack of medical understanding throughout the nineteenth century.

Whipple was born sometime in 1841 and served in the 24th Regiment, New Jersey Volunteers Company H in the Civil War from September 1862 to July 1863. On February 1, 1866, he married Clara H. Borden and had five children, with three living to adulthood. (2) His son, Oscar K. Whipple, joined the Whipple Store and become a partner in 1895. Together, they ran the business until March 22, 1910, when Whipple died and Oscar K. continued operating the store alone. (3) The Bridgeton Evening News printed a detailed obituary that ended with “In the death of Mr. Whipple, Bridgeton loses a substantial businessman and a patriotic citizen.” Several months after Whipple’s death, the Bridgeton Evening News later again printed a description of Whipple and his store, informing the readers that: “This is the only store in Bridgeton where one can procure the justly celebrated ‘Rexall Remedies’ and in fact. George H. Whipple & Son are dealers in the ‘best of everything’ in their line. A laboratory for the careful compounding of prescriptions is maintained at the highest standard of efficiency.” (4) The city appeared to have thought highly of their Mr. Whipple and George H. Whipple and Son Drugstore.

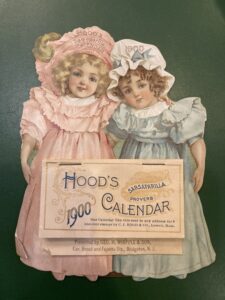

Rexall Remedies was potentially one of many patent medicines that were available at George H. Whipple and Son Drugstore. Another item with the Whipple’s name attached to it was Hood’s Sarsparilla, which was manufactured by C.I. Hood & Company in Lowell, Massachusetts, founded in 1875. Hood promised that their medicines could purify blood in addition to cure edema, heart disease, rheumatism, and a variety of other illnesses. (5) Patent companies promised to heal and improve society, yet their products were not as effective as they claimed. Instead, the medicines ultimately could only give consumers peace of mind, a sense of control, and at times a hangover due to the amount of alcohol contained in some of the medicines.

Society changed drastically as capitalism developed throughout the 1820s and 1830s, changing where people lived and their labor. Initially, apprentices had lived with their craftsmen who taught them how to make items. The process was then divided to speed up production with several people taking on different roles in the creation of an item, ultimately losing their ability to become a skilled artisan. The splitting of tasks and population growth in cities led to large-scale manufacturing and the introduction of factories. Due to the number of people, workers became disposable and work security scarce. Manufactured goods and printing developments led to businesses and companies creating needs and problems that sometimes had not previously existed to sell items. Individuals could be healed or transformed through a monetary transaction of new items, turning them into the person that they desired to be. Patent medicines were one of many items needed for society to become exactly who they wanted to be for a couple of dollars. (6)

Overall, American Society preferred patent medicine over treatment by trained medical physicians due to mistrust society had developed during the beginning of the nineteenth century. The popular practice of bleeding and bloodletting scared people from seeing a physician for treatment. The growth of anti-intellectualism also played a role in the distrust of physicians. Many came to believe that the “plain man of common sense seemed superior to the trained expert.”(7) Mistrust in trained physicians also derived from religion. Male doctors treating obstetrical cases was prohibited, as was anatomical study done by dissecting cadavers – both due to religious reasoning. Pseudo doctors took advantage of these insecurities, portraying themselves as being an “average joe” and further reaffirming the fear of expert doctors. (8)

Patent medicines were available in shops, at Wild West Shows, Carnivals, Traveling Medicines Shows, and from pitchmen. Performances served as large-scale advertisements aimed at inspiring desire and need for the medicines among potential customers. Racial imagery tended to be used in advertisements. Librarian Matthew Chase states that ” Traveling medicine shows relied a great deal on the advertising value of racial imagery, particularly in term of ethnic caricature performances.”(9) Entertainers often used blackface and redface during patent medicine performances. In some shows and ads, medicines were linked to Indigenous cultures and traditions or faraway countries such as China, Turkey, and Egypt. Society believed that the appropriation of cultures and traditions of Native Americans, of different countries, and ancient times made the medicines more effective. The use of racial imagery was also used in printed ads for patent medicines. Advertisements, pamphlets, and entertainment spread knowledge of patent medicines to large audiences. (10)

For the most part, ingredients were rarely ever listed on the bottles and containers of patent medicines, leaving the consumer ignorant of what they were consuming. Some concoctions contained large doses of alcohol and dangerous additives. Due to the questioning ingredients, some states began to crack down, forcing patent medicines to include a list of the ingredients on the bottles. Between 1905-1906, journalist, Samuel Hopkins Adams, wrote several articles on the horrors of nostrums, describing them as the “Great American Fraud.” Adam’s articles were compiled into a small book that aided in the passing of the Food and Drugs Act in 1906. The new act prohibited misleading or false information on the label regarding the ingredients or the identity of the drug. Six years later, the Sherley Amendment went further banning labels from including false and fraudulent claims. Educating the public was also an initiative to aid in combatting the use of harmful patent medicines. The Food and Drugs Act forced patent medicine companies to be transparent with their customers and helped in protecting the health of Americans. (11)

George H. Whipple and Son Drugstore was one of the many spaces that sold these highly desired patent medicines. Anti-intellectualism, distrust of doctors, religion, and lack of medical understanding made patent medicine the only viable option for treatment or sustainable health. Printing and cheap entertainment helped further spread knowledge and entice individuals to purchase patent medicines. During a time when medical treatment was still questionable and inaccessible for many, patent medicines offered some sort of comfort and give a sense of control during those times of poor health.

Sources:

-

- James Harvey Young, “Medical Quackery in the Age of the Common Man,” in The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 47, No. 4 (Mar., 1961), p. 579

- Find a Grave has George Henry Whipple as being born in August of 1841. There are many contesting accounts of his birth. Census records note his birthday as 1842 and 1843. Since the cemetery stone lists 1841 as his birthdate, I feel that that is the best date to use, but have not found sources to confirm August. Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/156861493/george-henry-whipple : accessed 30 January 2022), memorial page for George Henry Whipple (Aug 1841–22 Mar 1910), Find a Grave Memorial ID 156861493, citing Old Broad Street Presbyterian Church Cemetery, Bridgeton, Cumberland County, New Jersey, USA ; Maintained by Spaceman Spiff (contributor 46783007); “New Jersey, County Marriages, 1682-1956,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VWRS-P5Z : 23 February 2021), George H Whipple and Clara H Borden, 01 Feb 1866; citing Cumberland, New Jersey, New Jersey State Archives, Trenton; FHL microfilm 1,289,243.; “New Jersey Deaths and Burials, 1720-1988”,database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FZZN-KHZ : 19 January 2020), Carrie D. Whipple, 1873.; “New Jersey, Deaths, 1670-1988,” database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2SZ-1NFY : 15 May 2020), Jennie E. Whipple, 29 Mar 1867; citing Death, Bridgeton, Cumberland, New Jersey, United States, Division of Archives and Record Management, New Jersey Department of State, Trenton; FHL microfilm 004208606.; Bridgeton Evening News, March 23, 1910

- Bridgeton Evening News, March 23, 1910; Bridgeton Evening News, September 20, 1910.

- Bridgeton Evening News, September 20, 1910.

- Jessica Griffin, “Hood’s Sarsaparilla, Lowell, MA,” in Old Main Artifacts, (January 21, 2014), https://oldmainartifacts.wordpress.com/2014/01/21/hoods-sarsaparilla-lowell-ma/

- “A Market Revolution,” Smithsonian: National Museum of American History Behring Center, https://americanhistory.si.edu/american-revolution/market-revolution#:~:text=In%20the%201820s%20and%201830s,transportation%20like%20the%20Erie%20Canal.

- James Harvey Young, “Medical Quackery in the Age of the Common Man,” in The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 47, No. 4 (Mar., 1961), p. 581

- Ibid., p. 581

- Matthew Chase, “Cures and Curses: A History of Pharmaceutical Advertising in America,” University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, https://library.usa.edu/cures-curses-exhibit

- James Harvey Young, “Chapter 11: The Pattern of Patent Medicine Appeals,” in The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, March 8, 2015); Brooks McNamara, “Pitchmen, High and Low,” in Step Right Up, (University: University of Mississsippi, 1995), p. 19-42; Matthew Chase, “Cures and Curses: A History of Pharmaceutical Advertising in America,” University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, https://library.usa.edu/cures-curses-exhibit

- James Harvey Young, “Arthur Cramp: Quackery Foe” in Pharmacy in History, Vol. 37, No. 4 (1995), (American Institute of the History of Pharmacy), p. 176-182; J.W. Kille, in A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Nonclinical Drug Development (Second Edition), 2017, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/pure-food-and-drug-act

Further Sources:

https://melnickmedicalmuseum.com/2013/03/27/19ctreatment/

https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/149661

https://www.hagley.org/research/digital-exhibits/history-patent-medicine