See the World in a New Way: A Brief History of the Stereoscope

Tia Antonelli

For some time in the early nineteenth century, the eyes were a focal point of scientific research. Scientists were fascinated by what our eyes could do, both individually and in tandem with one another – what were the limits? What can someone see with two eyes versus one eye? During this period of interest, scientists discovered “binocular vision,” which is when a person with two eyes looks at an object through both eyes at once, and sees the object with more dimension as they see it with the left- and right-eye perspectives at once. In light of this revelation came the stereoscope.

A vintage portable stereoscope and stereoscopic slide, as on display at The Gibbon House, NJ.

The stereoscope was first invented in London, 1838 by Charles Wheatstone, and was a box-shaped device with eye-lenses, wherein one could look into the box and view images on stereoscope slides. These slides had two different perspectives of the same image, each situated in front of the eye-lenses, so when one looked into the box they would see a three-dimensional projection of the image. The development and success of the stereoscopes was concurrent with the development of photography; in order for the illusion to be effective, the images need to be essentially identical in everything aside from perspective. An artist can achieve this with simple figures, but it becomes more difficult as the images become more detailed and complex. (1) In the late 1850s, Oliver Wendell Holmes, a doctor and essayist based in the Northeast region of the United States, agreed that photography was a necessity for the stereoscope’s illusion, stating that “[t]he first effect of looking at a good photograph through the stereoscope is a surprise such as no painting ever produced. The mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture.” (2)

Wheatstone’s original stereoscope was roughly the size of a table. David Brewster changed the design to make it smaller, so one could bring the device up to their eyes, and this ultimately led to its increase in production and popularity, both throughout Europe and the United States. (3) In fact, some believe that the stereoscopic craze hit the U.S. harder than Britain. (4) They were still new to the states in the 1850s, one Ohio newspaper claiming it was a new invention by someone other than Wheatstone; however, as quickly as they appeared, the business boomed. (5) For the nineteenth century, this invention was a marvel. Frequently, it was used in schools for both science and humanities courses – as early as the 1860s, students in the United States would use them in addition to microscopes in biology classes, and to study maps in geography classes. (6) Albert E. Osborne, who wrote in-depth on the use of stereoscopes in education, claimed that “[a]lmost every child knows what a stereoscopic photograph is, its weight, and of what material it is made.” (7) This further suggests that students physically interacted with this technology and that they were commonly available in classrooms, which speaks to the growing popularity.

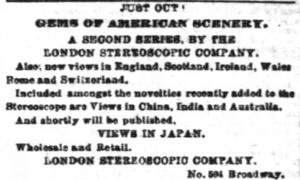

New York Times, June 16, 1860.

Additionally, stereoscopes provided entertainment. With a box and some slides, one could pretend they were traveling to other countries and see other sites without leaving the comfort of their own home. The Gems of American Scenery, for instance, advertised about 100 European scenes, and 40 Egyptian, as well as slides (or “views”) with photographs of scenic landscapes in the United States, for about $3-5 a dozen. During the Victorian era, a time of Western colonial expansion and rule, the idea of “exoticism” drew people in, so it could be that the stereoscope aided in fulfilling this desire, as one could go almost anywhere and see almost anything with little effort. Overall, people were highly satisfied with stereoscopes and their multiple uses, with one anonymous author writing “no description of ours will do justice to the beautiful results of the most beautiful of all the arts.” (8)

The stereoscope was a product of scientific discovery used to show the illusions of binocular vision, and was additionally utilized by people in Europe and the United States for general education and entertainment. Today, stereoscopic technology is still used in the medical field to view X-rays, as well as in entertainment. (9) The popular “View Master” toy, which Sawyer’s Photo Services debuted at the New York World’s Fair (1939-40), is essentially a re-imagined stereoscope, and the popularity of this toy has persisted for almost a century. (10) Additionally, the mechanics of 3-D movies are based upon stereoscopic technology. Despite stereoscopes being invented in the early nineteenth century, their presence and impact on the scientific, educational, and entertainment fields is still visible today.

Sources:

(1) Brewster, David. The Stereoscope; Its History, Theory, and Construction: with Its Application to the Fine and Useful Arts and to Education. United Kingdom: John Murray, 1856, 6.

(2) Holmes, Oliver Wendell. “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” The Atlantic, June 1859, 5.

(3) Thompson, “Stereographs Were the Original Virtual Reality.”

(4) Green, Harvey., Becker, Howard Saul., Southall, Thomas W.. Points of View, the Stereograph in America: A Cultural History. United States: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1979.

(5) “New Invention.” Ohio Observer, April 21, 1852. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

(6) “Resident Editors’ Department.: THE MICROSCOPE AND THE STEREOSCOPE.” 1864.Massachusetts Teacher and Journal of Home and School Education (1856-1871) 17 (2) (02): 73. and W, F. P. 1860. “XVI. EDUCATIONAL MISCELLANY.: NEW AIDS TO THE STUDY AND TEACHING OF GEOGRAPHY. WHAT IS GEOGRAPHY? A FEW PERTINENT EXAMPLES. OCEANIC INFLUENCES. WHY HAS NOT THIS METHOD PREVAILED? DESCRIPTION OF THE INDEPENDENT SERIES. PARTICULAR DESCRIPTION OF THE MAPS. ASIA AND PROFILES. EDUCATIONAL USES OF THE STEREOSCOPE. DEDICATION OF THE EVERETT SCHOOL-HOUSE. ADDRESS OF EDWARD EVERETT. FEMALE EDUCATION. THE LOWE PRINTING PRESS AND OFFICE.” The American Journal of Education (1855-1882) (23) (12): 623.

(7) Osborne, The Stereograph and the Stereoscope, 29.

(8) “MISCELLANEOUS.: SCIENTIFIC. THE STEREOSCOPE: ITS WONDROUS BEAUTY AND POWER.” 1859.New York Observer and Chronicle (1833-1912), Dec 22, 405.

(9) “Stereoscope | Optical Instrument.” Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d.

(10) National Museum of American History. “Sawyer’s View-Master,” Smithsonian Institute, n.d.